News & Stories

A time to heal

His mother died in May and his wife followed in June, but the Denver pulmonologist hadn’t let himself cry.

Instead, he went right back to his work combating COVID-19, the virus that killed those closest to him.

Then he visited “In America: Remember,” the 2021 art installation created by Suzanne Firstenberg (MBA ’83). There – on the National Mall in Washington, D.C. among a sea of white flags symbolizing each American life lost during the COVID-19 pandemic – he wept.

“He came up to me and said, ‘Suzanne, I had to put my doctor face back on and go right back in. Being here with the flags, I can finally cry,’” says Firstenberg. “That’s when I understood that this was something uniquely powerful.”

Lives lost

A year after she pulled up the last tiny white flag and talked to thousands of people who came to see her work, Firstenberg’s memories of “In America” are still visceral.

Image provided by Bruce Guthrie

There was the woman who brought her nephew to see the flag that represented her sister and his mother. He wrote a message on the flag for his mother, planted it in the ground and looked at his aunt and smiled. It was the first time she had seen him smile since his mother died.

There was the elderly woman from Phoenix who lost her husband and was comforted by a young mother from Atlanta. Another woman fell to her knees and sobbed. A stranger offered her a hug.

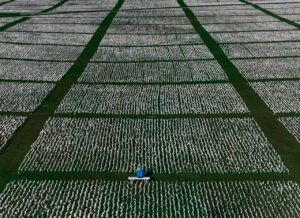

For 17 days, “In America: Remember” blanketed the National Mall with over 660,000 white flags on over 20 acres.

During that time, Firstenberg had to add about 2,000 flags a day as COVID-19 took more lives. Not all of the flags came with messages, but each one was a child or a spouse or a grandparent.

After she heard a statement that 170,000 deaths from COVID-19 were “just a statistic,” she created the first installment, “In America: How Can This Happen,” just months into 2020. Working with volunteers, she planted 165,000 flags on four acres outside the defunct Robert F. Kennedy Memorial Stadium in Washington. She then invited the public to plant more flags in the surrounding area.

They soon ran out of room.

Designed to evoke Arlington National Cemetery, the exhibition ultimately held 267,080 white flags, nearly matching the 270,000 headstones at Arlington.

Image provided by Jonathan Thorpe

Firstenberg worked closely with the U.S. National Park Service to bring the second installation, “In America: Remember,” to the area of the National Mall bordering the Washington Monument and the World War II Memorial.

The flags represented the cross-section of American lives lost. Some included brief messages of love. Others had full names and many were geotagged for a database of loved ones on the “In America” website. Each flag told a singular story of sorrow and anger, of what could have been and never will be.

Martin and Carolyn Howard were married for nearly 58 years and died 10 days apart. They share a flag.

“She was Dr. Mom, always a phone call away to help diagnose or listen to any problem we had,” reads a message on another flag. “I miss those phone calls.”

Takelya Bazemore was a registered nurse from Greensboro, North Carolina, whose flag noted “her passion to give the best care possible to anyone in her care.” She was 23 when she died.

Image provided by Dan Swartz

Firstenberg’s installation received massive media attention. The New York Times hosted a short-form documentary about “In America” that Firstenberg commissioned. Washingtonian magazine named Firstenberg one of the “10 Washingtonians of the Year.”

“There was a magic that happened in those flags,” says Firstenberg. “I knew that people would come together and support one another. I knew strangers would comfort strangers. I didn’t realize just how much solace the flags would provide. It gave people permission to grieve.”

An artist with an MBA

In October 2021, just a few weeks after “In America: Remember” ended, Firstenberg responded to a tweet that highlighted her work from UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School.

“Plenty of MBA skills were used to execute this immense project!” she responded.

“People are surprised to hear that I used those skills,” says Firstenberg, “but ‘In America’ was a very complex art installation. It took developing a team of volunteers, thinking about the product, the marketing, the experience. Thinking about how people were going to relate to the art. I was the right artist to do it because I had the business background.”

She was the right artist also because of her unique vision. She prefers being known as a social practice artist or a creator of art that’s socially meaningful.

“I don’t want to be an activist because I want to let the vehicle be the art,” she says. “It’s not about me. It’s about the topic.”

She’s unafraid to explore the depths of the human experience and some of the most divisive issues of our time: drug addiction, gun violence, climate change. She hopes people will engage with her art, consider different viewpoints and perhaps relate in a way they never have tried before.

“This is a place for people to experience the art and think about how to use art for positive social change,” says Firstenberg of her art studio in Bethesda, Maryland.

She’s busy preserving “In America.” Volunteers collected 20,000 flags dedicated to individuals for Firstenberg’s archives and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of American History collected a few for posterity.

Image provided by Bruce Guthrie

“What I wanted was for people to relate to each other through their grief, through the shared experience of the pandemic,” says Firstenberg. “I wanted this to transcend politics.”

Her life has uniquely informed her art’s mission. She has spent 25 years volunteering at hospices, so she knows how to sit with people in their grief. After college, she worked in new product development and marketing in the pharmaceutical industry, which helped inform her new opioid addiction series, “The Empty Fix.”

After she married and moved to Washington, she worked for then-Sen. Tom Daschle of South Dakota, her home state. She got an inside look at the political establishment and quickly became disillusioned.

“I was appalled that 80% of the time was spent posturing in politics and only 20% of it was substantively moving the ball forward,” says Firstenberg. “And I worked for one of the best senators on Capitol Hill.”

She didn’t work in Congress long, but subscribed to the Congressional Record, which chronicles activity on the House and Senate floors. She took those pages, turned them into 10,752 paper airplanes and created “Updraft America” for American University’s Katzen Museum.

She painted planes red and blue. The few issues outlined in the pages that crossed the political divide were colored purple and suspended in air flying above the rest.

“In this crazy environment, really over the past 20 years, people are often caught in these echo chambers of politics,” she says. “Art can gently and quietly filter in through the air vents and slide in under the door to unlock those echo chambers from the inside.”

Carolina confidence

Image provided by Bruce Guthrie

Anyone who wonders what an MBA from UNC Kenan-Flagler has to do with an art installation should look at Firstenberg’s “In America” organizational chart.

The center square represents the installation and herself. Some 30 spokes come off of the center with lines linking job titles, from marketers and volunteers to those handling publicity and fundraising. Squares noted website managers, lawyers, graphic designers and landscapers.

“It’s like what my organizational strategy professors would have wanted to see,” she says.

After graduating with a business degree from the University of Kentucky, Firstenberg chose the Full-Time MBA Program at UNC Kenan-Flagler and quickly knew it was the right choice. Watching Michael Jordan play basketball sealed the deal.

“It was like someone opening up a book of secrets,” says Firstenberg. “I just felt as though I was being so empowered with knowledge — and it made sense to me. I loved that.”

In Professor Gerald Bell’s class, she learned not just about organizational behavior but about herself. He had his students write their life stories, share them with a classmate and identify the central themes.

“There’s a self-confidence that comes from being a UNC student. To have a school ask you to turn in within yourself, it makes space for that confidence,” Firstenberg says. “Who could not be more confident when they come out of a high-ranking program like UNC Kenan-Flagler better understanding themselves?

“The program really prepared me to do whatever I wanted to do,” she says. “It opened my eyes.”

She’s been back to visit many times since graduating, including in the spring of 2022 when she spoke at the Ackland Art Museum. Her son graduated from Carolina in 2019.

“There’s just something about UNC,” she says. “Even people who didn’t go to UNC see it and understand it. It’s much more than just the beauty of the place. It’s just magical.”

Rising above

On the last day of “In America: Remember,” people surrounded Firstenberg as she pulled up the final flag.

Image provided by Jonathan Thorpe

A woman was standing off in the distance, just outside of her car. She had wrapped her arms around herself, and she was crying. Firstenberg went to her and introduced herself.

The woman, Cynthia, had planted a flag for her mother and she wasn’t ready for the flags to disappear. She was the person who a stranger hugged after she was spotted on the ground next to her mother’s flag.

Firstenberg invited Cynthia to her studio to talk. Their political and social views couldn’t be more different but they talked almost three hours straight and came to an understanding on some divisive topics.

“Grief brought us together. Grief was the common element, but so was respect for others, the dignity of others,” says Firstenberg. “We have to find ways to relate to others to transcend politics. It’s time. What I really want to do is encourage people to move beyond, get out of the trenches.”

Art doesn’t often have that effect. Firstenberg’s does.

Article image provided by Jonathan Thorpe