News & Stories

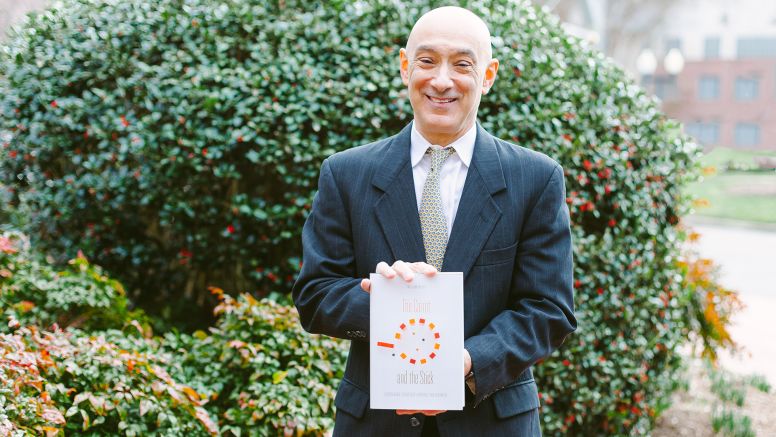

Using a “Carrot and a Stick” strategy to compete

Being successful in an isolated part of the market is not enough in today’s business environment.

The new game is one of competition across different markets: Find and access points of strategic control in one industry that you can leverage across multiple industries.

William Putsis, professor of marketing at UNC Kenan-Flagler, provides a strategic guide to win that game in “The Carrot and the Stick: Leveraging Strategic Control for Growth.”

He explains how to spot and own points of strategic control, extend them to multiple markets, and vertically align incentives that leverage the control point for superior margins.

“The ‘carrot’ refers to the concept of aligning upstream and downstream incentives – those of suppliers and customers — to be compatible with your own,” says Putsis. “It involves setting up your entire value chain and customer-incentive structure so that they are in their best interests to do what’s in your best interest.”

“The ‘carrot’ refers to the concept of aligning upstream and downstream incentives – those of suppliers and customers — to be compatible with your own,” says Putsis. “It involves setting up your entire value chain and customer-incentive structure so that they are in their best interests to do what’s in your best interest.”

The “stick” represents a strategic control point within a part of a market that, if controlled by one party, can be leveraged for greater margins. It can be in the supply chain, a related business or even in an unrelated market.

Perhaps the best – and most dramatic – example of a strategic control point is SoftSoap®, the liquid hand soap. In the 1980s, the Minnetonka Corporation started offering “Crème Soap on Tap” through boutique distributors. The product was a success and the corporation followed up with a similar version for mass retail sale.

The small manufacturer knew it would face tough competition to get its product on shelves and industry giants such as Procter & Gamble, Johnson & Johnson and Unilever could easily attempt to imitate its success. Minnetonka leaders believed that a 10- to 12-month head start could give them enough time to build up enough brand presence and shelf space allocation to maintain a one-third market share – even after the big players entered.

How did they buy that time? Through a strategic control point: Minnetonka bought up the world’s supply of plastic pumps. If any major manufacturers wanted to enter the liquid soap market, they would have to wait until the pump supply built up again – or build their own factories to make them, which would take at least eight to 10 months. Pump manufacturing was a classic strategic control point – a part of the supply chain that, when controlled, enabled SoftSoap® to gain a differential competitive advantage in the key part of the market – retail – it was pursuing.

When firms do an exceptional job of aligning vertical incentives and using strategic control points, they win, says Putsis. “Research shows that such companies’ earnings before interest, taxes and amortization (EBITA) more than doubled from 2009 to 2016, with almost 70 percent share price appreciation).”

He identifies these carrot-and-stick strategies to gain unique competitive advantages:

- Extend from industries to ecosystems: Industries are often interconnected in ways we’ve never before seen – an ecosystem that allows for competitive advantages and avenues for growth into adjacent markets. For example, Local Motors, which additively manufactures (3D prints) automobiles, has developed a 3D printing platform with a wide range of interconnecting value chains and interconnected industries. It can leverage its capabilities in designing, building and selling 3D-printed automobiles into countless manufacturing applications, industries and industry value chains. It produces 3D-printed microwave ovens for GE and helps Airbus create revolutionary part-supply networks.

- Find points of leverage in a value chain: Find an area in short supply, where competition is low or where barriers to entry are high, and you might be able to exploit them for superior margin. Look for situations where – if your firm controls certain capabilities – you can make it difficult for others to effectively compete. While competitive advantages often result in an arms race in which you need to continuously work to stay one step ahead of the competition, a point of strategic control is often enduring and considerably more powerful. An example is a pharmaceutical company with a patent, such as Pfizer’s patent on Viagra when it first came to market.

- Align incentives among separate parties: When looking for a point of strategic control, the supply of critical input to another party could be a source. Information is a prevalent access point, thanks to cloud-based interconnectivity (the Internet of Things). In the wind-energy industry, a few companies are installing sensors in windmills to detect motor failure, allowing its partnering windmill manufacturing firms to dispatch repair teams before the motors fail. The firms installing the sensors own exclusive access to the data generated, and they leverage it by selling maintenance contracts to the manufacturers or farm owners. Because the manufacturers can’t efficiently do this themselves, there is a win-win scenario that maximizes windmill up time and provides peak efficiency.

- Decide where to compete before deciding how to compete: Companies can leverage strength in one market to their competitive advantage in another. The key is finding a direct connection between your unique capabilities in your core market and a critical strategic control point in another. Think of Amazon taking its supply chain expertise into multiple markets.

For people who have spent their careers competing in the value chain, working the production system or compelling the sales team to squeeze margin in an intensively competitive industry, there’s a new way to win, says Putsis.

“The identification of these opportunities is key in the interconnected business environment of today. It essentially represents the difference between success and failure.”