News & Stories

Remembering two titans of industry

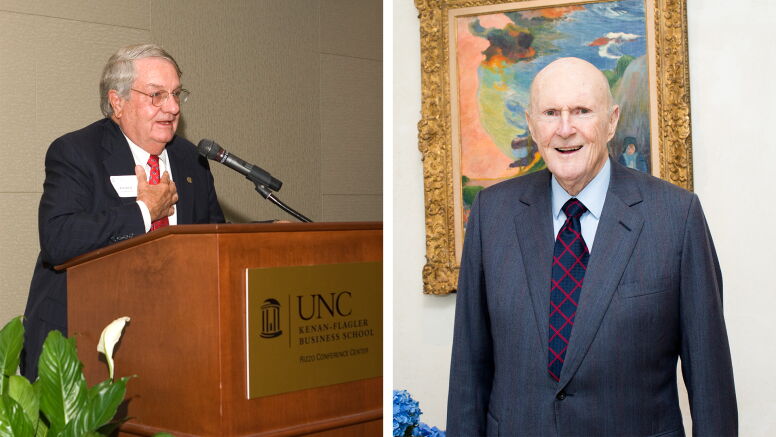

Two titans of industry died in August after well-lived lives and making a lasting impact on the business world and UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School.

Charlie Loudermilk (BSBA ’50), Atlanta’s iconic business and civic leader and founder of Aaron Rents Inc., died at age 95 on Aug. 2, 2022.

Julian Robertson (BSBA ’55), the pioneering hedge-fund manager and founder of Tiger Management, died at the age of 90 on Aug. 23, 2022.

“We have lost two extraordinary members of our community,” said Dean Doug Shackelford (BSBA ’80). “As alumni, their success made us proud. As leaders, they changed their industries and contributed to their communities. And through their philanthropy, they touched many lives at UNC Kenan-Flagler and in the cities where they lived.”

Who is Aaron?

Lowdermilk was an entrepreneur, philanthropist, business and community leader and consensus builder who made an indelible impact on his beloved Atlanta. At UNC, he was a deeply engaged alumnus who generously shared his talents, wisdom, and philanthropy and whose life embodied the School’s core values of integrity, inclusion, innovation and impact.

Lowdermilk was an entrepreneur, philanthropist, business and community leader and consensus builder who made an indelible impact on his beloved Atlanta. At UNC, he was a deeply engaged alumnus who generously shared his talents, wisdom, and philanthropy and whose life embodied the School’s core values of integrity, inclusion, innovation and impact.

Born and raised in Atlanta, Lowdermilk enrolled at Georgia Tech when he was 16 and left to serve in the U.S. Navy in World War II. He came to UNC where he studied business and after he graduated in 1950 and worked as a salesman for Pfizer in Greensboro, he soon decided he wanted to work for himself and returned to Atlanta.

In 1955, he founded Aaron Rents with $500 when he identified a market gap for rentals – tables, chairs, linens, silverware for – weddings, funerals and entertaining. As his business grew, he adjusted to renting office and residential furniture, appliances and electronics.

Countless times people asked him: “Who is Aaron?” His answer: “There never was an Aaron. I just wanted to be the first name in the Yellow Pages.”

He went on to develop a unique lease-to-own model with a vision to fill a void for the underserved customer by providing the best deal on the highest quality products. The company offers its services through multiple channels to approximately 40-50% of the U.S. population who have an annual household income under $50,000. Today Aaron’s is a $3 billion rent-to-own giant in name-brand furniture, consumer electronics and home appliances through its 1,300-plus company-operated and franchised stores in 47 states and Canada.

Lowdermilk stepped down as CEO in 2008 and then as chairman in 2012 when he was 85.

According to the Atlanta Business Chronicle, some of his most significant contributions to Atlanta came through his friendship with Andrew Young, a minister and civil rights leader who served as U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, mayor of Atlanta and a U.S. Congressman.

“Few since the 1960s, when Atlanta began to emerge as an economic engine in the South, have united Black and white business leadership as well as Loudermilk and Young,” according to the Atlanta Business Chronicle. “It began with a friendship stemming from Loudermilk’s support of the 1965 Selma to Montgomery march in Alabama to register Black voters.”

Lowdermilk got to know Young when he rented tents to the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) for that march. Young, a close confidant to Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., was the SCLC executive director. The experience had a profound effect on Lowdermilk and deepened his involvement in the civil rights movement.

He went on to co-chair successful mayoral campaigns for Young in 1981 and 1985, which made Lowdermilk unpopular with many of his friends. “But that was their problem, not mine,” he said. The Washington Post wrote about their enduring relationship in “They Kept Atlanta Too Busy to Hate.”

Lowdermilk was instrumental in bringing the U.S. Olympics to Atlanta, and his philanthropy was a major force in the city he loved, with his family estimating he donated more than $35 million to causes across Georgia.

He also was a generous supporter of his alma mater. He helped fund construction for the McColl Building, where the Loudermilk Foyer in front of Koury Auditorium is named in his honor, and for the Rizzo Center, where UNC Executive Development offers programs in Loudermilk Hall. He also donated the funds to build Kenan Stadium’s Loudermilk Center for Excellence, which serves Carolina’s student-athletes across 28 sports.

He shared his expertise by serving on the UNC Board of Visitors and the Carolina First Campaign committee. He received the Board of Trustees’ William Richardson Davie Award and the Richard A. Baddour Carolina Leadership Academy’s Leader of Distinction Award.

During the 2015 University graduation ceremony, UNC awarded Lowdermilk an honorary Doctor of Laws degree for both his philanthropy and his role in the civil rights movement. As dean of the school from which he graduated, it was Shackelford’s honor to spend much of that weekend with Lowdermilk, who shared numerous stories about Carolina, Aaron Rents and Atlanta, and at one point, he mentioned “Martin.”

With some hesitation, Shackelford asked if he was referring to Dr. King. Lowdermilk then told him about their relationship. He said that both were young fathers in Atlanta trying to establish themselves – he in the business community, Dr. King in his ministry. Together they formed a group of young Black and white leaders who met regularly in the hope that friendship across racial lines could help Atlanta avoid the violence and tragedy affecting many cities then. Regarding Aaron Rents providing tents and other support for the Selma march, he matter-of-factly stated that Dr. King had the funds, so he supplied the goods.

“Not every white businessperson back then acted as courageously as Charlie did,” said Shackelford. “He will always be a hero of mine.”

Hedge-fund pioneer

Robertson was a hedge-fund pioneer, a tremendous mentor and a generous philanthropist.

Robertson was a hedge-fund pioneer, a tremendous mentor and a generous philanthropist.

The Financial Times called him “one of the most influential hedge fund managers of all time” who “achieved heroic status both for his record at New York-based Tiger Management during the early days of the hedge fund industry and for the dynasty of hedge fund traders known as the ‘Tiger Cubs’ that he helped launch.”

Robertson was born in Salisbury, North Carolina, on June 25, 1932. After he graduated from Carolina, he spent two years in the U.S. Navy and then moved to New York in 1957 to join Kidder Peabody & Co., eventually become CEO of its asset-management arm. In 1978, Robertson and his family spent time in New Zealand, where he created three major resorts.

When they returned to New York, Robertson left Kidder Peabody and started Tiger Management in 1980 with $8 million in funds and built it into one of the world’s largest hedge funds with $21 billion under management before he closed his funds in 2000.

Forbes chose him as one of the 100 greatest living business minds in 2017. The financial press reports that almost 200 hedge firms can trace their start to Tiger Management and funds run by Tiger Cubs have earned billions of dollars for investors.

“The true success of Robertson and Tiger extends beyond the stellar performance numbers and mind-boggling assets under management,” Daniel Strachman wrote in “Julian Robertson: A Tiger in the Land of Bulls and Bears.” “Ultimately, the success of the firm can be measured in the legacy of his cubs.”

Tiger Cub Philippe Laffont, founder of Coatue Capital, said Tiger’s focus on hiring “people who were well-rounded instead of specialists” was the “special sauce” that “created a culture of people who were competitive, curious and extroverted,” according to the Financial Times.

Robertson shared what makes good portfolio managers in a 2010 UNC Kenan-Flagler alumni magazine. They have to be “smart, honest and have the courage of their conviction. In addition to that, we have found that competitiveness is an important factor.” They also need “honesty and smarts. Wall Street and the rest of the world are looking for people who want to make this a better place than it was when we arrived.”

“No shop in the history of investment management has produced more phenomenal people,” Dixon Boardman, chief executive of Optima Asset Management, who worked with Robertson at Kidder, Peabody & Co., told the Financial Times.

“We were young and hyper-competitive analysts competing against people [in other firms] who worked seven-hour days and were used to two-martini lunches,” Tiger Cub Lee Ainslie (MBA ’90), a managing director of Tiger Management before he founded Maverick Capital. “Julian was a mentor and a friend to so many people who aspire to live up to his example as both a great investor and an extraordinary philanthropist.”

John Townsend (BA ’77, MBA ’82) retired as a senior advisor with Tiger Management in 2015 after more than 30 years in investment management and banking. “He was one of the legendary investors of the last 50 years,” Townsend told Business North Carolina. “To start my career with one icon [UNC graduate Dick Jenrette] and end it with another, both from North Carolina, is a real highlight for me.”

During his lifetime, Robertson contributed more than $2 billion to charity, according to the Financial Times. He started Tiger Foundation to support low-income New Yorkers and their families and it has provided more than $250 million in grants to help schools, employment training programs and childhood education, according to its website. “Julian Robertson is one of the few hedge fund managers I admire as much for the way he’s used his money as for the way he made it,” said George Soros, the most prominent of the hedge fund pioneers, in The New York Times in 2016, referring to his philanthropy as well as his investment culture.

Robertson endowed a premier fellowship for our Full-Time MBA Program, which recipients reflect on in this 2018 video. Among them is Tiger Cub Dwight Anderson (MBA ’94), Ospraie Management founder, who talks about working with Robertson.

The School awarded the Alumni Leadership Award to Roberson for his exceptional career achievements in 2011, and he received the Distinguished Service Medal Citation from the UNC General Alumni Association in 2005. The award read: “Julian does credit Carolina with giving him a very good understanding of accounting. It might be too much to claim that he learned here all he needed to manage what became the world’s largest hedge fund, but he believes that those accounting courses he somehow squeezed in were an important foundation for his future success.”

That award also cited the program founded by Robertson and his late wife, Josie, in 2000, when they donated $24 million to create the Robertson Scholars Leadership Program to encourage collaboration between Carolina and Duke and promote the development of young leaders. He told The Wall Street Journal: “I have intense respect for both great institutions. But I am rooting for Carolina, of course.”

He got the idea after his son, Alex (BA ’01), matriculated at Chapel Hill and his son, Spencer, graduated from Duke a few years earlier. Alex is now president of Tiger Management and Spencer is the founder and CEO of PAVE Schools. His third son, Jay, is CEO of Robertson Lodges in New Zealand, where Robertson’s $181 million art collection will move to the Auckland Art Gallery.

Business and UNC also were family matters his sister, Wyndham Robertson. The first female assistant managing editor at Fortune, she returned to North Carolina in 1986 to become the first woman vice president in the 16-campus University of North Carolina System and served as vice president for communications for 10 years.

Read more about Charlie Lowdermilk in this Atlanta Business Chronicle article.

Read more about Julian Robertson in this New York Times article.