News & Stories

Changing minds – and lives

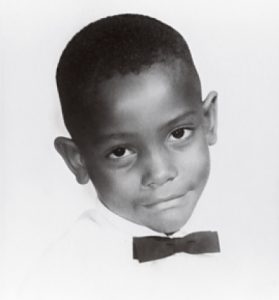

Work started at age 5 for James H. Johnson Jr., who grew up on a tobacco farm outside Greenville, North Carolina.

Johnson, who is the William R. Kenan Jr. Distinguished Professor of Strategy and Entrepreneurship at UNC Kenan-Flagler Business School, picked up workers’ mid-morning and mid-afternoon drinks and snacks from the local country store during the harvest season.

He could already add and subtract, and when the store clerk gave him back the change, Johnson kept a few coins for himself, he says. “I never made the right change for the workers. But it wasn’t because I couldn’t count. Rather, it was the price of doing business.”

Johnson’s parents set up a bank account for him and mandated he set aside some earnings for clothes. They let him buy new outfits twice per year – before school started and during the President’s Day sales. Instilling a work ethic and helping Johnson manage money would carry him throughout his life, he says.

Johnson’s parents set up a bank account for him and mandated he set aside some earnings for clothes. They let him buy new outfits twice per year – before school started and during the President’s Day sales. Instilling a work ethic and helping Johnson manage money would carry him throughout his life, he says.

“I never knew we were poor until I got to college and started studying poverty,” says Johnson.

Changing the world

That realization and his upbringing led Johnson to the path of becoming an educator and activist.

He grew up in North Carolina during segregation. The Black and white parts of town were literally separated by railroad tracks, a signal of who could go where and a symbol of the economic divide. Johnson’s school received used books from the white schools, and Johnson remembers getting used books that were worn, torn and racist language written in the margins.

His grandmother advised him to persist and never take a backseat to anyone.

“I can hear my grandmother now saying, ‘You put your pants on the same way they do,’” says Johnson.

Schools integrated when he started high school, but tension remained. Years of segregation led to what sometimes seemed like an insurmountable divide.

“You would be sitting next to kids whose parents your parents worked for,” says Johnson.

When he left for college, he headed to North Carolina Central University (NCCU), a historically Black university (HBCU) in Durham. The experience shaped him by providing a valuable education in African American history and an impetus for his dedication to teaching the next generation.

“I wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for attending an HBCU,” says Johnson. “It gave me a keen sense of my history, self-worth and self-concept.”

Character is destiny

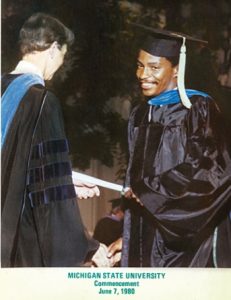

After Johnson graduated from NCCU, he earned his MS from University of Wisconsin at Madison. After he earned his PhD in geography from Michigan State University, he joined the faculty of UCLA.

After Johnson graduated from NCCU, he earned his MS from University of Wisconsin at Madison. After he earned his PhD in geography from Michigan State University, he joined the faculty of UCLA.

While there he wrote a grant proposal to create a UCLA research center to study poverty and inequality. He won more than the $6 million grant.

An anonymous reviewer of the grant proposal was Jack Kasarda, then a UNC sociologist and director of the Frank Hawkins Kenan Institute for Private Enterprise. He called Johnson and asked what it would take to get him to come home to North Carolina and work at UNC.

“I still had in my mind the North Carolina of segregation,” says Johnson. “So, when he asked me what I wanted, I gave him a long list of things that seemed impossible.”

It was 1989, and Johnson had a class to teach, so he ended the call – but the story didn’t. UNC never gave up, and Johnson decided to return to his home state – drawn by his family and his desire to make a difference.

Back then, Johnson called his grandmother every Sunday. She insisted he call at 9 a.m. sharp even though it was 6 a.m. where he was in California. During one conversation, she was sweltering in a North Carolina heat wave and admitted that her air conditioning had been broken for a year and she never told anyone. Johnson felt the pull toward home. It did not hurt that UNC was making an offer he could not refuse, he says. By 1992, he moved to Chapel Hill.

“There was an opportunity to do something about the issues I cared about,” he says. “I could stop just writing about them and make change.”

Seeing the future

In 1997, before diversity and inclusion were talking points for business leaders, Johnson began teaching workplace diversity. As a trained demographer, he saw disruption on the horizon.

“We were in the midst of an impending demographic shift,” he says. “I saw this impending wave of change was coming and built a course around it.”

He continues to teach Managing Workplace Diversity to MBA and Master of Accounting students. The class shows future leaders how to survive and thrive in a diverse environment, where people come from different backgrounds and have different perspectives. He talks to students about the iceberg model of diversity in which you see 30% of the iceberg and miss everything that’s underneath.

He continues to teach Managing Workplace Diversity to MBA and Master of Accounting students. The class shows future leaders how to survive and thrive in a diverse environment, where people come from different backgrounds and have different perspectives. He talks to students about the iceberg model of diversity in which you see 30% of the iceberg and miss everything that’s underneath.

“I’m a Black man from the Boomer generation,” he says. “You don’t know what you don’t see.”

By using the power of storytelling, Johnson lifts the iceberg, gets personal and shares how has lost 10 family members over the last decade. He makes the point that everyone in the class might not have lost as many people, but most have lost at least one.

When students talk about their own experiences, they find they are more similar than they are different. For example, the Black male student who can’t get a taxi on Fifth Avenue in New York can relate to the Palestinian student who has faced the same kind of discrimination trying to purchase a one-way plane ticket, says Johnson.

In the early days, some pushback meant Johnson had to argue in favor of keeping this course as an elective. Now, the discussion is about finding space for this class in the core curriculum.

Paying it forward

Johnson has spent the bulk of his career examining and testing strategies for successfully educating children who live in areas of concentrated poverty. He teamed up with the late philanthropist Frank Hawkins Kenan to put his studies into action and continues to do so today.

Globe Scholars circa 2017

He co-founded the Global Scholars Academy, a K to 12 school in Durham, and the Minority Male Bridge to Success Project, an initiative of the Business School in partnership with the academy to improve college access for young males of color.

“What drives me is making sure these young people have the same opportunities or more opportunities than I had,” says Johnson.

To start, he asked the question, “How do you apply business concepts to education to make it more inclusive and equitable?”

Before the school ever launched, Johnson created the Durham Scholars Program, which was effectively an after-school camp that provided resources and mentorship for promising students, who then could receive college scholarships. He found that 80% of those students graduated high school and 50% went on to college. Over 15 years, the program helped transform the lives of 240 young people growing up in impoverished neighborhoods.

The Durham Scholars Program led to the Global Scholars Academy, which is delivering innovative education ideas. For example, the school is open year-round from 7:30 a.m. to 6 p.m., and faculty teach students Mandarin Chinese beginning in kindergarten.

“We expose students to the opportunities that are going to be there for them in the future,” says Johnson. “You are going to lose your shirt if you ignore these trends.”

Reveling in every success and working tirelessly to ensure no one falls through the cracks, Johnson wants any student with a desire to further his or her education to be able to do so. Recently, three young men from the Global Scholars Academy won full scholarships to one of the nation’s most prestigious boarding schools.

Johnson and Payne at a 2019 awards ceremony

Some students who work with Johnson end up at UNC. Kyle Payne (MBA ’17) had been held back and labeled as having attention deficit disorder. Johnson believed in him and thought he might have just been bored with school because he wasn’t being challenged. Payne was among the first Durham Scholars and went on to earn his BA at Carolina, his MIS at NCCU and his MBA from UNC Kenan-Flagler.

Payne has worked for Volvo, Blue Cross-Blue Shield and Bank of America. Johnson highlighted Payne’s successes when he won the Leadership Award from UNC Kenan-Flagler.

“It’s all about the kids,” says Johnson.

Move between the suites and the streets

Johnson, who is the director of the Urban Investment Strategies Center at the Kenan Institute, also teaches New Urbanism, an MBA course about smart growth, sustainable living and the creation of more equitable and inclusive communities. Johnson wants his students to have the opportunity to apply what they are learning. They work in teams and always have clients.

In his pursuit of inclusion, Johnson is spearheading the development of metrics to rank businesses and cities based on how equitable they are. A series of town halls in places like Washington, D.C., Maryland and Virginia will provide insight into how cities can transform and respond to the issues that are coming to the forefront because of the Black Lives Matter movement and the pandemic.

His commitment to making change through research and advocacy extends into the legal system. In the early 1990s, he devised a death penalty mitigation strategy, which has been used in many cases involving Black men, and published several papers on the topic. He has testified in some 60 related courts cases in across the U.S.

Johnson continues to study disruptive demographics and the ways businesses must adjust to become more equitable and prepare for the changes ahead. Taking the science of demography and translating it through white papers, op-eds and talks around the U.S., he addresses the economic implications of the “browning” and “graying” of America – the two colorful demographic processes he says will transform the workforce, workplaces and consumer markets – as well as immigration, whole community health, encore entrepreneurship and foresight planning for sustainable economic development.

In an era of turbulence and enormous uncertainty, he says, leveraging diverse talent and embracing diversity of thought are the keys to survival, viability and prosperity in our hyper-competitive global marketplace.

Never taking anything for granted

Johnson remains focused on creating equity in education, driven by his devotion to family and his experiences.

The influence of his parents, grandparents and wife are evident. In the last 10 years, Johnson has lost all of them. In 2004, his wife died from cancer at age 48. Although he was deep in mourning, he never missed a class.

“I promised my late wife that I would keep the school going,” he says. “So, that’s my focus.”

He is tireless when it comes to his work, but doesn’t forget what is really important in life. He advises people to make relationships their priority and forget about sweating the small stuff.

“There are pressing social problems we should be addressing, and I had to do something,” as he told Fast Company. “I’ve always believed I was put on this earth to make a difference.”