Thought Leadership

How to Increase the Odds of People Paying Attention to Your Communication

George Bernard Shaw said, “The single biggest problem in communication is the illusion that it has taken place.” Are you under a similar illusion? I have coached a lot of leaders who are frustrated that they are not being heard. I often hear leaders say, “I told them, so why don’t they get it?” The questions I usually ask include, “How many times did you tell them?” And, “How clear was the communication?” It has been proven that the message sent is not always the message received. But when our text messages say “delivered” after they go through, we fall victim to the illusion that communication happened. The metaphor of a mailbox is compelling for our communication — I can send a communiqué, but I cannot assume it will be received, opened, read, or understood.

So, what can you do? First, increase the amount you are communicating. The marketing rule of seven states that potential customers need to “hear” a message at least seven times before they will buy a product or service. I have found the same in business communication. Why? It takes time to get people’s attention, develop trust, get our meaning to rise above the noise of other messages, and compel people to action. With everyone’s overloaded newsfeeds, inboxes, social media, and more, it is likely that people need to hear a message 7-10 times and in 7-10 different ways (e.g., face-to-face presentation, email, video, newsletter, all-hands meetings).

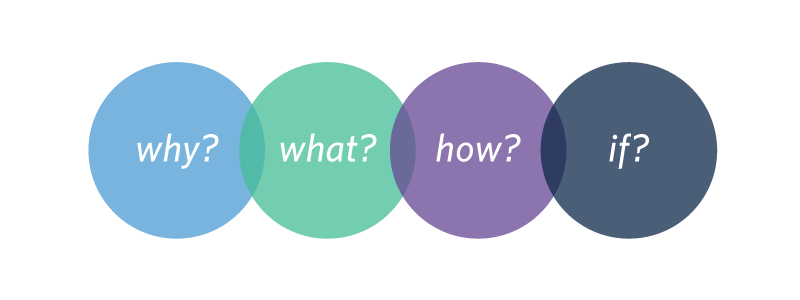

A second way to ensure your communication sent is actually received and acted upon is to improve the clarity of the message. A few years ago, I was asked by a client to teach Bernice McCarthy’s 4MAT System to help leaders improve their ability to communicate with employees. While the model was developed to help create more dynamic learning, it is a great framework to help leaders deliver information in a more complete and engaging way. McCarthy found that there are four distinct ways of taking in new information: experiencing, conceptualizing, applying, and creating. Translated simply for communicators this becomes: Why? What? How? If?

When preparing your communication, you should consider questions in these four areas:

Why is this important? Why is this relevant to me? Why should I pay attention to this?

Listeners need a reason to engage and the rationale behind what you are saying. In effect, you are pre-empting their internal dialogue of “So what?” and “Why should I care?”

What are the facts? What does the data say? What exactly are you asking me to do?

Listeners need to hear the facts and gain some understanding before they will be willing to try it out or commit to implementing. Consequently, it is important to give the rationale and thinking behind the facts and details.

How will this work? How will I use this in my work? Will I be able to do what you are asking?

Once listeners know the specifics and associated logic, they want to try it out, experience it, and potentially even give it a test run. This is where they want to “kick the tires” so to speak. And this is where leaders hear, if they are open, where the speed bumps are in the work of their employees.

If this is true, then what? If I do this, what will be better? If I modify your idea, what will happen?

It is likely that your communication will not cover every situation or contingency. It would be too long and detailed if it did. Consequently, listeners need permission to consider alternatives or to adapt it to their work environment. They need to know the guardrails and what authority they have to implement the ideas in their area. When employees start asking the “If” question, it leads to engagement because employees will start to make it their own.

A natural reaction to communicating this way is: “I do not have time to communicate this much and prepare all of this!” I get it. Usually, I will craft what I am trying to say, and then quickly scan to see if I have covered all four areas. Then I look to see how many other times I plan on sharing the message. We are all busy, but I have found that a little time upfront saves me a lot of time later answering questions and clarifying what I tried to say. To get started, use this simple 6-step process to make your communication more effective and better received:

- A little what? Provide just enough what so people know what you are talking about.

- Why? Give them the WIFM (What’s in It For Me).

- What? Present the essential facts, data, logic, and conclusions.

- How? Offer a chance to “try on” the idea in a safe way (even if it is just questioning, testing, and discussing with a co-worker).

- If? Ask: “What do you think? What do I need to know? What questions do you have? What will it take to implement?”

- When? When will you share this message again? Are there other ways to deliver the same message besides the one you have just prepared?

Make Yourself Heard

If you care that the message you send is the message received — and understood and implemented — spend a little time upfront increasing the odds that people will pay attention to what you have to say. Answer the questions they will ask either to you directly or silently to themselves. And make sure your communication is heard enough times that it rises above the noise of everything else vying for your employees’ attention.

SOURCES:

Jacob Morgan: “Research Shows Only 8% Of Leaders Are Great Listeners And Communicators.”

Inc.: “Harvard Psychologists Reveal the Real Reason We’re All So Distracted”

Adapted from Tim Sanders, The Likeabilty Factor